To celebrate a new paper out in Bayesian Analysis, let’s talk simulation-based calibration checking (SBC). SBC is a method where you use simulated datasets to verify that you implemented you model correctly and/or that your sampling algorithm work. It was introduced by Talts et al. and has been known and used for a while, but was considered to have a few shortcomings, which we try to address. See the paper or the documentation for the SBC package for a precise description of how that works. We also ran a tutorial on SBC with all materials publicly available.

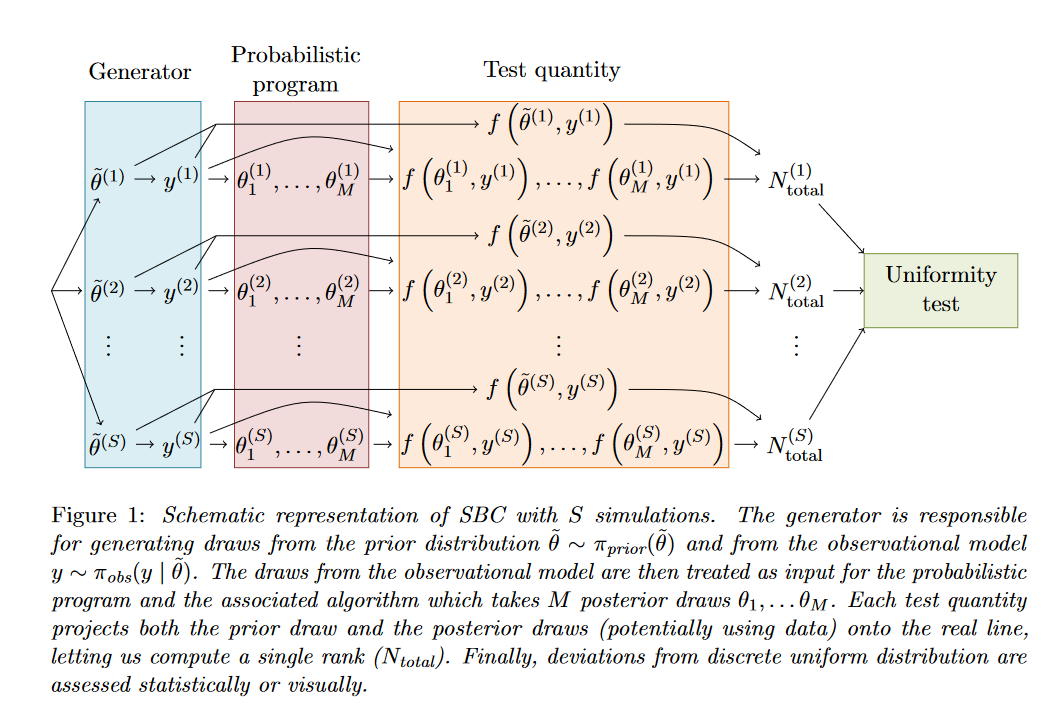

But in short, the basic idea is that you implement your model twice: beyond a probabilistic program (e.g. in #Stan, #jags, …) + a sampling algorithm you also need a simulator drawing from the prior distribution - this tends to be easy to implement. You then simulate multiple datasets, fit those with your probabilistic program and compute ranks of the prior parameter values withing the posterior. If you did everything correct, the ranks are uniform. Non-unifomity then signals a problem.

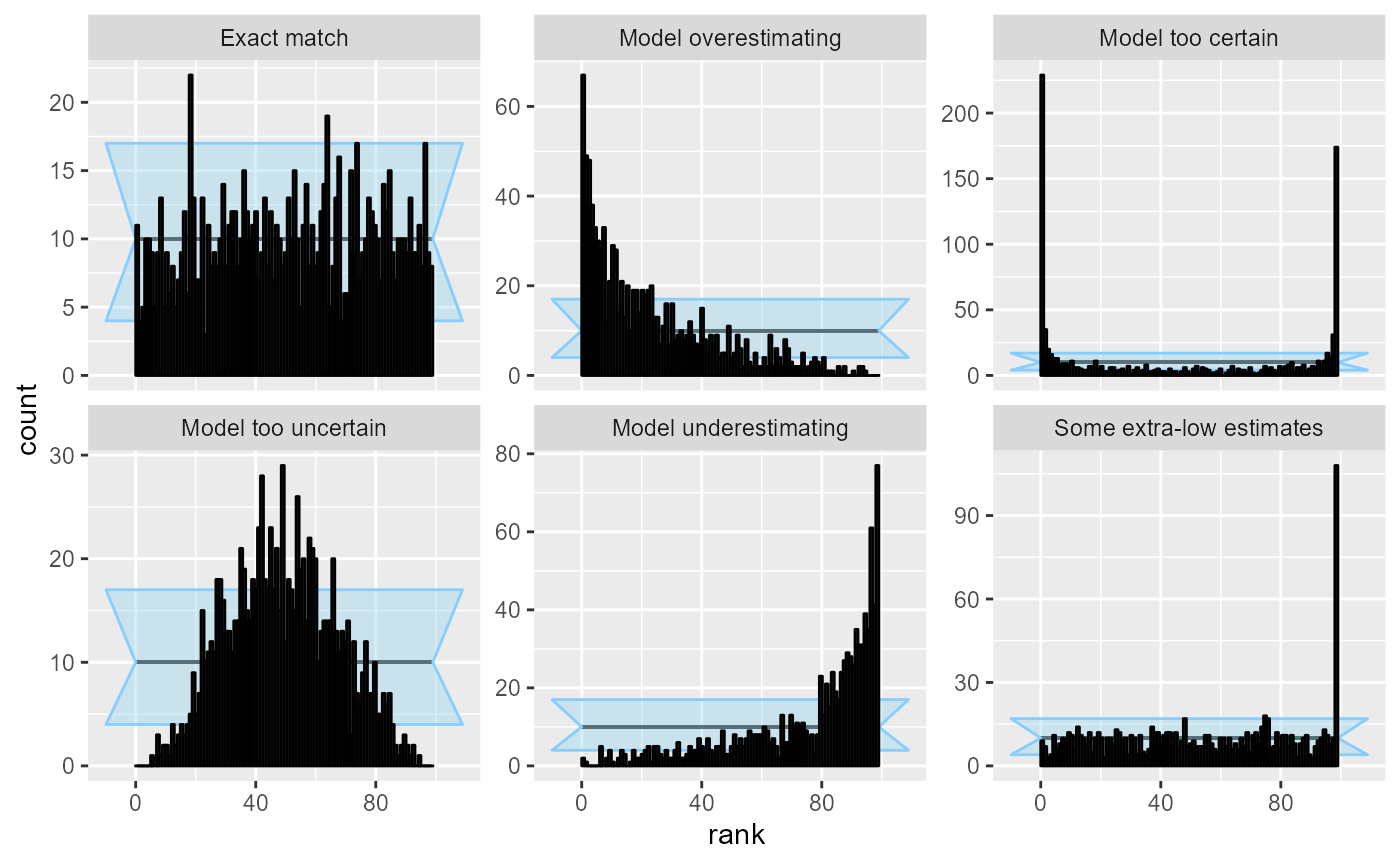

The gist of our new paper is that strength of SBC depends on the choice of “test quantities” for which you compute ranks. The default approach is to take all individual parameter values. This is already a very useful check, but it leaves a big class of bugs you can’t detect (e.g. when posterior is just the prior distribution). However, when you add derived test quantities, combining the parameters with the simulated data, you can (in theory) detect any problem! (Yaaaay!) But in theory you may need infinitely many quantities :-(.

In practice, it seems to be quite sufficient to add just a few additional test quantities beyond the default. In particular, our experience as well as theoretical considerations indicate that the model likelihood is very sensitive. The power of SBC is still limited by the number of simulated datasets you can reasonably fit which primarily limits how big discrepancies can go undetected.

More generally, we provide a firmly grounded theoretical analysis of SBC which will hopefully help others to build better intuition on how and why it works in practice. Notably, we make it clear that SBC does not check whether “data-averaged posterior equals the prior” as is sometimes claimed in the literature (and as I also was convinced when starting this project :-D )

The SBC package supports all of the ideas discussed in the paper in R. I personally now use SBC for almost all my Stan work from the get go – although there is some extra work to setup SBC, you end up detecting bugs early and thus save time in the long run. If you want to see an example of simulation-driven model development workflow, check out the Small model implementation workflow vignette.

This work was made possible by generous help from Angie H. Moon, Shinyoung Kim, Paul Bürkner, Niko Huurre, Kateřina Faltejsková, Andrew Gelman and Aki Vehtari.